Preventing Self-Harm: What You Should Know if You Want to Offer Help

Seeing that a teen has unusual scars that may be the result of self-harm can be jarring for many people, who may not know how to respond. But to those who hurt themselves, the act is straightforward, says Susan Lindau, adjunct professor with the Department of Adult Mental Health and Wellness at the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work. Someone experiencing deep psychological pain self-harms to find temporary relief from mental anguish.

Many times, “the emotion is so overwhelming, so painful, that self-harm is used to take the consciousness off of the psychic pain and onto the physical,” Lindau said.

In other words, the physical self-harm diminishes the psychic pain because the individual can see the impact as well as feel the injury which often distracts from the overwhelming emotional pain, she explains.

For those who want to intervene, simply wrapping their minds around the concept of self-harm can be a challenge. But understanding the intention for self-harm can increase a person’s empathy and ability to help those in need, she said.

What Is Self-Harm and Why Do People Self-Harm?

Self-harm can be classified in a number of ways, but many health experts refer to self-harm as nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI). NSSI is the deliberate injury or damage of one’s body without suicidal intent. Behaviors that cause injury but are considered more culturally and socially acceptable, such as piercings and tattoos, do not generally fall under the category of NSSI. Common forms of NSSI include:

- Cutting

- Scratching

- Burning

- Biting

- Carving

- Hitting

- Punching

- Head banging

These actions are maladaptive coping mechanisms for regulating particularly negative emotions such as pain or anger. Lindau, who has a private practice working with severely depressed, chronically suicidal individuals, said people who self-harm can sometimes have similar physical and psychological responses to their behaviors as people with addictions do when they have the urge to drink alcohol or use drugs. Those with eating disorders also experience similar psychological relief through their behaviors, she added. These behaviors all fall into the category of addictive behaviors.

In a 2018 meta-synthesis of qualitative studies of self-harm among young people, researchers set out to decipher the purpose of self-harm as understood by the person engaging in the act. They identified four overarching functions:

Functions of Self-Harm as Understood by the Person Engaging in the Act

1. To obtain release or relief from a burden or intense feeling.

Adolescents said that self-harm acted as a necessary release from pressure or distress. In some cases, they expressed self-hate. However, others described the act as allowing them to experience a rush of positive feelings, similar to an addiction, or simply to feel alive.

2. To gain control over and cope with difficult feelings.

Adolescents explained that acts of self-harm enabled them to rid themselves of emotional pain sometimes associated with traumatic incidents. It was described as giving them a sense of control when feeling alienated or helpless; it could help them feel numb or neutral.

3. To represent unaccepted feelings.

Adolescents described difficulty finding the right words to express their feelings and assert themselves. They expressed a desire to protect friends and family from their feelings and from finding out that they were engaging in these behaviors.

4. To connect with others.

For some adolescents, self-harming allowed them to connect to a group who share similar problems and feel like outsiders, too. It was also used to express pain to others and ask for help.

Life is complicated, especially for adolescents, Lindau said. And many of them are dealing with serious issues like divorce, their first relationships and peer pressure to drink. But it’s imperative to underscore that self-harm is never an appropriate way to deal with problems.

“We need to teach them how to manage a crisis,’” Lindau said.

What Is the Prevalence of Self-Harm?

A 2011 study on self-harm found that the prevalence of lifetime NSSI among adults in the United States was approximately 5.9 percent, with 2.7 percent reporting that they had engaged in NSSI five or more times. Just under 1 percent said that they had engaged in NSSI in the past year.

However, prevalence is higher in younger populations. A 2012 international meta-analysis of 52 studies indicates that about 17 percent of adolescents engaged in NSSI at least once.

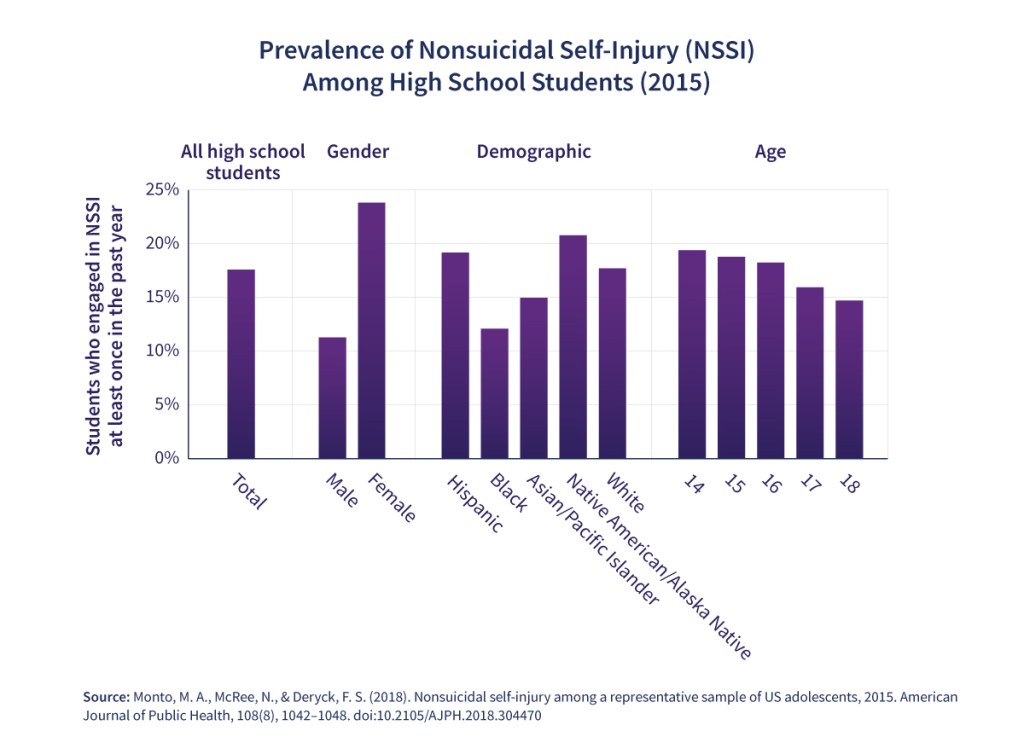

In another 2018 study, researchers specifically looked at NSSI among high school students in the United States. They found that about 18 percent of high school students engaged in NSSI in the past year, with the prevalence higher among girls (23.8 percent) than boys (11.3 percent).

The same study provides details on the association between NSSI and specific health risks for high school students. Drug and alcohol use, fighting, cyber-bullying, being forced to have sex and identifying as a sexual minority were all associated with NSSI. Depression, suicidal thoughts, making suicide plans and suicide attempts were similarly associated with engaging in self-harm.

The Connection Between NSSI and Suicide

In a literature review published in 2016, authors examined the connection between NSSI and suicide. NSSI and suicidal behaviors share a number of risk factors including depression, substance misuse, posttraumatic stress disorder, history of abuse or violence, and family dysfunction. Frequent NSSI itself and some specific types of NSSI are also highly ranked risk factors for suicide.

One subtheme of the review is Thomas E. Joiner’s interpersonal theory of suicide as one potential explanation for how NSSI can lead to suicide. Joiner theorizes that people need both the desire to die by suicide and the capability, but most people fear physically hurting themselves. Multiple acts of self-harm erode that fear and pain, increasing a person’s capability to harm themselves and eventually die by suicide.

How Can You Help if You See Someone Engaging in Self-Harm?

There are often telltale signs a person is engaging in self-harm. Lindau said to be on the lookout for the following signs:

They have red cuts, burns, gashes or bruises on their hands, wrists, stomach or thighs. These are common sites of self-harm; however, self-injury can happen anywhere on the body.

They engage in other unusual physical behaviors such as chronic hair pulling or self-damaging itching and picking that leads to serious bleeding, bruising and scarring.

They wear long-sleeved shirts and other clothing that covers up their body in warm weather — a sign they may be covering up self-inflicted cuts and burns.

They follow social media accounts that promote self-harming behaviors and share links to self-harm how-to videos.

Treatment for NSSI can often involve individual or group therapy and usually begins after the patient has undergone a psychological evaluation to determine whether they have depression or suicidal thoughts. The evaluation will help to assess what stressors may be contributing to the patient’s perceived need to self-harm and what functions self-harm is serving. If the patient needs specific treatment for underlying mental health conditions, those are treated first.

Therapy focuses on behavioral interventions, teaching skills such as emotional regulation, self-management, mindfulness and effective communication to fill the needs that self-harm serves in a healthy way. Educating friends and family is an important component of treatment because they can help to make safety plans and implement de-escalation strategies.

Self-Harm Intervention Strategies for Loved Ones

Self-harming behaviors are serious and require the help of a professional, but there are things loved ones can do to support someone who is self-harming. The MSW@USC asked Lindau for strategies that family and friends can employ if they know someone struggling with self-harm.

Improve Communication

- Encourage them to talk about their issues with you, a therapist or even an online resource or support hotline.

- If you’re a parent, pry. Do not ignore your gut. Say, “I’m worried about you. Let’s talk about what’s going on,” and “I may be a worrywart. Tell me what’s going on.” Or, “You haven’t told me as much as you usually do,” and “Can you show me your arm? I am afraid you might hurt yourself.” Hostile response can be expected.

- Don’t ask them why — it puts people on the defensive. It’s better to say, “I hear you — how do you feel about that?”

Provide Distraction

- Help them replace self-harming behaviors with physically healthy behaviors, such as a brisk run or intense 20-minute workout. Encourage them to practice self-care, such as taking a bath, when the urge to self-harm rears up. Even sticking your face in a bowl of ice water can shock the impulse part of the brain and stop the momentary desire to self-harm. The idea is to take the focus off of self-harm long enough for the intense urge to self-harm to diminish.

- Teach STOP: Stop what you’re doing. Take a deep breath. Observe what it felt like to take that deep breath. Proceed with what you were doing.

- Practice paced breathing together. Find a quiet place and focus on measured breathing and counting in and out for 10 minutes. You’ll probably see results within three minutes.

Get Help

- If they’re an adult and the urge is overwhelming, tell them to drive to the emergency room and sit in the waiting room for an hour; if the urge to hurt themselves does not diminish after about an hour, they should register with the front desk and ask for professional help. “We have to help them learn to manage the urge to self-harm,” Lindau said.

- If you see blood, take them to the doctor or your nearest urgent care facility or emergency room for professional help. Remember, if a person’s self-harming behaviors are escalating and have become life-threatening, supporting them at home isn’t enough.

If you or somebody you know needs help, there are a number of places you can reach out to for assistance:

- The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, which can be reached at 1-800-273-8255.

- The National Hopeline Network, which can be reached at 1-800-442-4673.

- The Trevor Lifeline, which can be reached at 1-866-488-7386 and offers services for LGBT individuals.

- The Crisis Text Line, which can be contacted by texting “HOME” to 741741.

- To Write Love on Her Arms, which offers tools to help locate mental health resources in your area.

Note: This article has been published for informational purposes only and does not represent a medical opinion. If you or a loved one are exhibiting signs of self-harm, you should consult with a mental health professional.

The following section includes tabular data from the graphic in this post.

Prevalence of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury (NSSI) among High School Students at least once in the past year (2015) ↑

| Demographic Category | Percentage of students who engaged in NSSI |

|---|---|

Total | 17.59 |

Male | 11.29 |

Female | 23.83 |

Hispanic | 19.19 |

Black | 12.1 |

Asian / Pacific Islander | 14.98 |

Native American /. Alaska Native | 20.79 |

White | 17.17 |

Age 14 | 19.4 |

Age 15 | 18.79 |

Age 16 | 18.25 |

Age 17 | 15.96 |

Age 18 | 14.72 |

Source: Monto, M. A., McRee, N., Deryck, F. S. (2018). Nonsuicidal self-injury among a representative sample of US adolescents, 2015. American Journal of Public Health, 108(8), 1042–1048. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2018.304470

Citation for this content: The MSW@USC, the online Master of Social Work program at the University of Southern California.