Nonconsensual Image Sharing Isn’t Pornography — It’s Sexual Assault

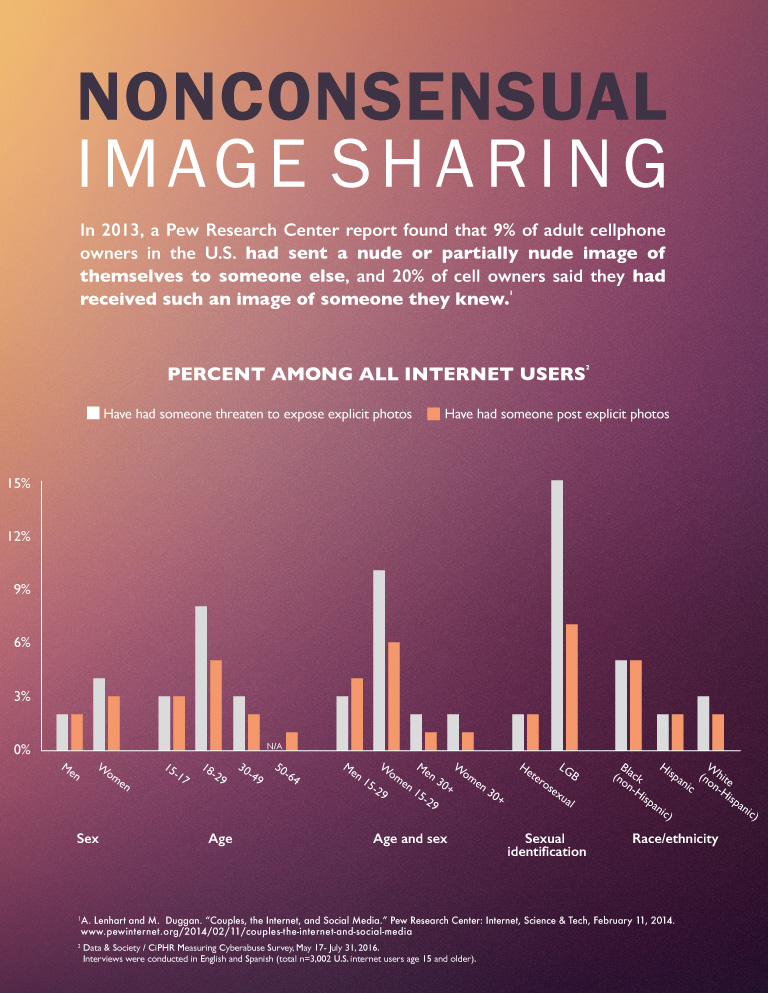

Celebrities — they’re just like us. In the case of having private or personal photos posted for public consumption without consent, celebrities like Jennifer Lawrence and Leslie Jones are just like many Americans. Approximately one in 25 Americans has either had a nude or nearly nude image of them posted on the Internet without their permission or has had someone threaten to post an image or video, according to a 2016 study from the Data & Society Research Institute and the Center for Innovative Public Health Research.

In the rapidly changing digital landscape, people are constantly finding new forums and quicker methods of sharing exploitative images of people to a boundless online audience. Some call it nonconsensual image sharing, some label it image-based sexual assault, and many use the term “revenge porn.” Regardless of the terminology, survivors of this growing form of exploitation share symptoms similar to survivors of physical sexual assault, underscoring the need for more effective strategies to end this abuse.

“It has all of the raw ingredients of sexual assault or sexual trauma,” said Jessica Klein, an adjunct lecturer with the MSW@USC, who specializes in trauma treatment with survivors of sexual assault. “The unique factor is the level of humiliation and shame is in many ways compounded …. It’s so public; it’s so known to others.”

The Mental Health Effects of Trauma

Few studies have been conducted on the effects of having nude or sexually explicit images posted online without permission. However, a qualitative interview-based study in 2014 and 2015 of 18 survivors published in Feminist Criminology shed light on the similarities between how revenge porn and sexual assault can affect a person’s mental health. Researchers in the study found a number of similarities between survivors’ experiences, including:

- Loss of trust.

- Self-blame.

- Post-traumatic stress disorder.

- Crippling anxiety and clinical depression.

- Suicidal thoughts.

- Low self-confidence and self-esteem.

- A sense of lost control over one’s body.

“That is essentially the defining issue of sexual trauma psychotherapy. Sexual trauma is an individual losing control over their bodies and their boundaries,” said Kristen Zaleski, a clinical associate professor with the MSW@USC, who has worked for more than a decade with sexual assault survivors in both inpatient and outpatient settings. “When your image is blasted over and over again, how can you feel safe being in places not knowing if other people have seen that vulnerable image of you?”

Zaleski noted that this form of sexual abuse, like others, is also a means for perpetrators to exert power and control over those whose images they share. Women and lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) people are more likely to be targeted with this form of exploitation.

According to the D&S study, one in 10 women under 30 have been threatened with nonconsensual image sharing and six percent reported having had someone post a nude or nearly nude photo online, higher than the rates for men the same age. Seventeen percent of LGB Americans have either had an image shared or been threatened.

View text-only version of this graphic.

Survivors interviewed in the 2014-2015 study published in Feminist Criminology coped with the stress in a variety of ways including denial and avoidance, excessive drinking, and obsessing over why their partner would target them or whether the perpetrator would take further actions against them. Victim blaming and online rape culture can also impact how survivors cope with abuse.

“With every new app being created, tons of websites, tons of forums, the comments sections of newspaper articles online — anywhere you go, you are inundated with people’s opinions about an act of sexual violence,” said Zaleski, who recently published a study on rape culture in online comments. “The social world survivors live in can interfere with their own version of how they feel about what happened to them and how they are going to go about their future.”

The D&S study also found that seeking out counselors and therapists, as well as relying on strong family and friend networks, helped survivors on their road to recovery. Klein, who has specifically worked with survivors of image-based sexual assault, uses similar treatment models that she uses with other post-traumatic survivors — creating a sense of safety and stability, managing symptoms, processing what happened and reconnecting with a greater sense of self. She particularly focuses on the shame and humiliation aspect, as well as working through what it means that these images are out there and what it means moving forward.

Relationship Realities in the Digital World

“As social workers, we need to adapt to the reality that our clients are using this technology,” Klein said. “There is enough trading of sexually explicit pictures that the answer is not to tell them to stop because that would just alienate them from us as clinicians. How can they make decisions based on their own integrity?”

A 2016 Kinsey Institute study of single adults found that 16 percent of adults reported sending sexual photos, while approximately 23 percent reported receiving sexual photos. Klein said that sending nude or sexual photos can be a part of healthy sexual expression within a loving relationship. The focus, however, should be on affirmative consent — making sure that those who send photos want to send photos.

“Is this a big ‘yes’ or is it an ‘I’m afraid he’ll break up with me if I don’t [send a nude photo]’ kind of thing?” Klein noted.

She added that couples who are in agreement to move forward should have an open discussion about how they are going to protect themselves down the line.

There also needs to be a greater sense of cultural dialogue around nonconsensual sharing of images, said Zaleski, who lamented that in high-profile cases of revenge porn, people question the victim’s decision to take photos rather than why a person would violate the trust of someone that they loved.

The Kinsey study also found that 73 percent of participants were uncomfortable with the sharing of sexual text messages beyond intended recipients, but 23 percent of those who received photos shared them with others. Zaleski said breaking through the disconnectedness of online platforms and social media and reminding people to treat images as any other trusted secret that a person would be expected to protect is the key to preventing violations. And bystanders who witness these acts cannot be afraid to speak up.

“You might not be a victim of it, but you need to stand up to the ones who victimize others,” she added. “Don’t just stand by and watch this happen.”

To learn about how to advocate for stronger laws against revenge porn, visit the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative. CCRI offers a number resources for survivors including an online removal guide, a list of individual attorneys across the United States who have volunteered to assist victims, as well as a 24-hour crisis helpline which victims can reach at 844-878-2274.

Citation for this content: The MSW@USC, the online Master of Social Work program at the University of Southern California.