How to Support Students Reentering the Classroom After Facing Severe Disciplinary Actions

For students who have faced disciplinary action that has forced them to leave their traditional school for a period of time and attend an alternative school, returning to familiar hallways may initially feel like a fresh start.

But while the student may have moved on from the incident that led to the disciplinary action, their teachers and peers may still view them through the lens of the behavior that occurred the last time they were in the classroom. Rather than getting a fresh start, students are walking into a time machine.

“Even if there’s this groundbreaking change within students, they are still facing an uphill battle to prove that they’re different, and people are also holding them to a higher standard,” said Terence Fitzgerald, clinical associate professor at the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work and expert in educational policy and institutional racism.

u003cpu003eu0022Even if there’s this groundbreaking change within students, they are still facing an uphill battle to prove that they’re different, and people are also holding them to a higher standard.u0022u003c/pu003e

Enabling students who have faced disciplinary action to successfully return to their schools requires collaboration and attention from many stakeholders including parents, teachers, school social workers and staff. It also requires a critical examination of the biases that adults in the school system carry, which can influence how students are perceived and disciplined, particularly young Black males.

What Racial Disparities in Disciplinary Actions Exist in Schools?

According to Fitzgerald, one of the most telling signs of racial inequity in education is discipline.

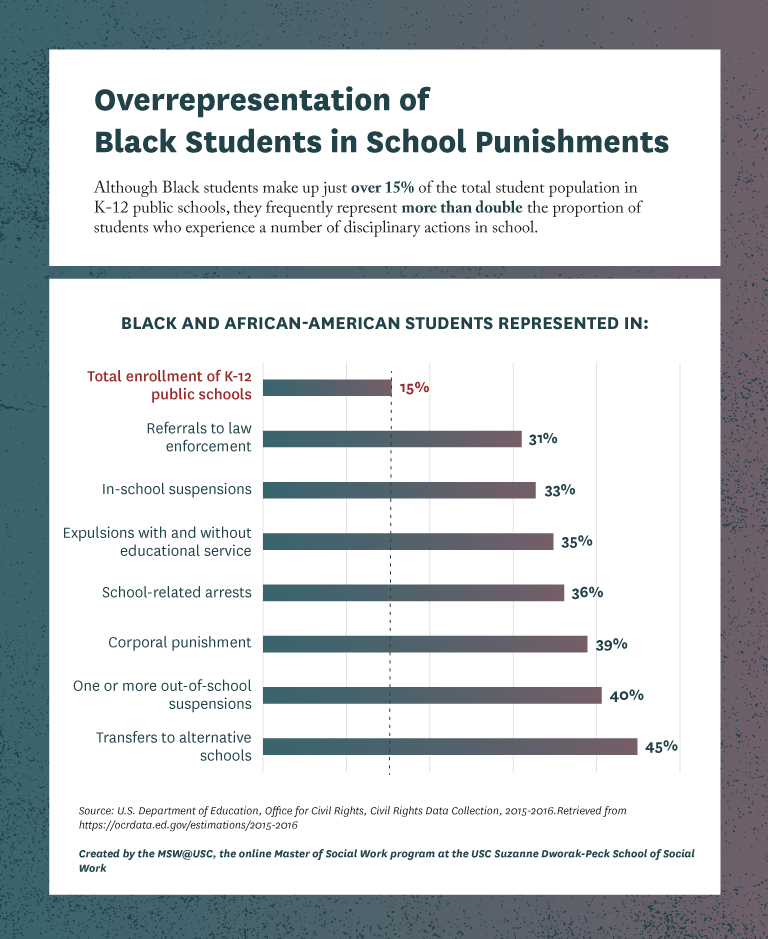

While Black and African American students represented approximately 15.4% of the student population enrolled in K-12 public schools during the 2015–2016 school year, they represented at least double the proportion of students who were subject to various disciplinary actions, including referrals to law enforcement, in-school suspensions and expulsions, according to 2015–2016 national estimations from the Civil Rights Data Collection. Of students who had been transferred to an alternative school, where they could continue their education while addressing behaviors that resulted in disciplinary action, Black students represented almost 45% of that population.

Why Are Black Males Subjected to Harsher Discipline in Schools?

“The manner in which [Black males] have been demonized historically relates to our treatment today,” Fitzgerald said.

Historically, Black males have been perceived as a threat, he explains, which has had significant implications in arenas such as the criminal justice system, judicial system and education system. And that perception extends to Black children, who he points out are often described as having adult-like traits and are disciplined accordingly.

“The imagery or the view of Black males doesn’t all of a sudden change as they get older,” Fitzgerald said. “The disproportionate discipline numbers indicate that this perception of Black males starts as young as pre-K.”

He adds that this perception has existed for so long that people have become desensitized to how it can harm children, especially as it warps to fit cultural standards.

“The horrifically beautiful thing about racism is that it morphs and isn’t overt all the time,” Fitzgerald said. “It has transformed into something that’s more palatable to the eyes and ears of non-Blacks today. This form is harder to point to as blatant and purposeful. But, as the physical harm that targeted Blacks during the civil rights era, this transformed and easily defended racism harms the social, emotional, and academic well being of Blacks with the same intensity as the former.”

Severe disciplinary action can have significant consequences for students that extend beyond the four walls of the classroom. Penalties can affect:

- Academic performance

- Social and behavioral skills

- Potential for employment

- Involvement with the criminal justice system

WIth regard to the criminal justice system, Fitzgerald also worries about the effects of adding more school resource officers in educational spaces, a suggestion which frequently surfaces after a violent incident like a school shooting.

“The conversation ignores what the ramifications are of the presence of the police on populations that have been marginalized,” he said. “The same things that are happening in our streets — the inability of the police to communicate, to see people of color as human beings — these are the same individuals we’re talking about bringing into our schools where our children are.”

How Are Alternative Schools Used to Address Disciplinary Incidents?

Tens of thousands of students are moved to alternative schools each year, according to 2015–2016 national estimations from the Civil Rights Data Collection. Although alternative schools were originally conceptualized as educational settings that could be more responsive to the individual needs of students who were having difficulties in traditional classrooms, a ProPublica report found that alternative schools are now primarily tasked with educating students who have disciplinary incidents, which can range from serious offenses, such as violence, to minor offenses, such as profanity or cell phone use.

Students who are sent to alternative schools do not get comparable educational experiences to those of their peers in traditional school settings, Fitzgerald says. Teachers in these schools are often less qualified and experienced, curriculum may not align with traditional schools, and alternative schools lack resources, such as libraries, technology and gym equipment, to give students the full educational experience.

Additionally, students are walking a tightrope trying to ensure that they don’t backtrack on progress. Fitzgerald explains that students may work hard in these schools to learn without disciplinary incidents in order to slowly earn back privileges. But one misstep can negate all of that work toward regaining the opportunity to return to their regular classes, friends, extracurricular activities and social activities.

“What kind of motivation would you have to proceed forward, continuously being knocked down?” Fitzgerald said. “I might as well settle in and be exactly who you say I am, because there isn’t a way out of this. So, if you deem me as the fool, you deem me as the dangerous one, you deem me as damaged, then I will become what you see me as.”

The discipline protocols in these schools are not designed to help children in the ways that they need, he says, and students would be better served in traditional schools by school social workers and school counselors who can listen to and understand their individual needs in order to address the root causes of behavior that can lead to disciplinary action.

“We need more champions for our children,” Fitzgerald said.

What Help Do Students Need to Successfully Return to a Traditional School?

For students who are able to transition out of an alternative school, returning to the traditional classroom can be a challenge. But a successful reentry can be achieved with collaboration involving the home school, parents, teachers, administrators and school staff.

“You have to have a concrete plan, not just abstract,” Fitzgerald said. “It has to be something in writing where people are held accountable.”

Fitzgerald suggested six strategies to collaborators working to create a plan for a student’s successful transition.

6 Strategies to Help a Student Transition Back to the Classroom

1. Monitor the student’s progress at the alternative school and identify potential reentry dates.

A team from the student’s home school, including a social worker and counselor, should designate a liaison to obtain regular updates on the student’s behavioral and academic progress at the alternative school.

2. Establish a clear line of communication for all adults involved in the behavioral reentry plan.

Parents and stakeholders from the home school and alternative school should schedule routine meetings with the social worker and set specific goals. This can include identifying what behavioral interventions will be used at the home schools, learning how to measure effectiveness of interventions, and selecting dates for progress reports.

3. Create an academic reentry plan.

Teams from the home school and alternative school should discuss any gaps in academic coursework with parents and create a specific plan to address those gaps. They should pinpoint deficits, identify teachers or tutors available to work with the student in areas of concern, schedule any extra lessons and create a plan to measure progress.

4. Ensure the student is in the optimal classroom settings for success.

The school team should identify teachers who have had success with students in similar situations and assign the student returning from alternative school to one of those classrooms, as opposed to teachers with whom they have had previous incidents. The school support team also should inform teachers about the academic and behavioral progress the student has made and identify any challenges that should be addressed.

5. Evaluate the effectiveness of the reentry plan.

Hold the student, teachers and staff accountable for following the behavioral and academic plans as outlined and make sure they are attending scheduled classes, appointments or meetings. Identify any new or returning behavioral issues and determine if there are any academic gaps that have been overlooked. Quickly address any problems that arise.

6. Implement a respite plan when necessary.

Design plans for teachers and students to help handle situations that have the potential to escalate to disciplinary incidents. When these situations arise, teachers may agree to allow a student to leave the classroom and meet with their social worker to refocus. The student should have a clear understanding that the requirement to return to class is a consultation with a social worker or school counselor.

The complex nature of this transition process underscores the need for more school social workers who can work directly with parents to ensure that they are involved in all of these steps. Parents can play an important role in holding schools, teachers and their children accountable, but they may not understand their rights or the specific terminology educators and administrators use, and they may be overwhelmed by the process. That’s where social workers can step in to help.

“Social workers are the front line in schools,” Fitzgerald said. “They’re there to advocate, they’re there to champion, they’re there to translate, they’re there to speak for the parents and children, but also speak for the schools and the needs of the schools to the parents and the children. They are a bridge, and we don’t have enough of them in our schools today.”

The following section contains tabular data from the graphic.

Overrepresentation of Black Students in School Punishments

Although Black students make up just over 15% of the total student population in K-12 public schools, they frequently represent more than double the proportion of students who experience a number of disciplinary actions in school.

| Black and African-American students Represented In: | Percentage |

|---|---|

Total enrollment of K-12 public schools | 15.4 |

Referrals to law enforcement | 31 |

In-school suspensions | 32.7 |

Expulsions with and without educational services | 34.8 |

School-related arrests | 36.1 |

Corporal punishment | 38.9 |

One or more out-of-school suspensions | 40.6 |

Transfers to alternative schools | 44.9 |

Source: U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights, Civil Rights Data Collection, 2015-2016. Retrieved from https://ocrdata.ed.gov/estimations/2015-2016

The MSW@USC, the online Master of Social Work program at the University of Southern California.