How to Address Suicide Prevention in High Schools

When USC Professor Ron Avi Astor finished watching “13 Reasons Why,” he, like many other professionals in his field, had concerns about how the show portrayed suicide. An expert in bullying and school violence, Astor worried the show sensationalized suicide, placing too much emphasis on what was going on in the school and not enough on individual mental health. Skeptical of the show’s premise, he set out to do a school-level analysis of nearly 800 high schools throughout the state of California.

What he found surprised him.

“I had this image of these kids coming in with a lot of mental health issues that the school didn’t know about,” said Astor. “I didn’t quite think the composition of students in the school setting was contributing so strongly - much stronger than most of our theories and prior studies suggest – to suicidal ideation to the extent that it is. And it is. So I was wrong.”

A new study published in the Journal of Pediatrics by Astor and his colleagues, Dr. Rami Benbenishty, a professor at Bar Ilan University, and Dr. Ilan Roziner, a departmental advisor at Tel Aviv University, found that nearly 1 in 5 high school students in California experienced suicidal ideation, a number that is high, but also consistent with many other studies on suicidal ideation among adolescents in the nation. However, the new study, the first to have a school level analysis, found that the level of suicidal ideation varies greatly from school to school, with some high schools reporting as low as 4 percent, while others reached nearly 70 percent.

“Look for schools with extremely high rates of suicidal thoughts, focus on them, and provide resources to help them engage in preventive work.”

— Dr. Rami Benbenishity, a professor at Bar Ilan University

“Imagine trying to teach math and it’s not getting through to the kids and your test scores are down because of this invisible barrier, not known to the school staff,” Astor said. “Half the children in the class may not be thinking about what you are teaching them; they are actually thinking, ‘How am I going to die and where am I going to do it?’ When we presented data back to principals, superintendents and teachers about students in their schools and school districts, you see them tearing up and crying because it’s not just an abstract happening in somebody else’s school. They then know these are students in their schools.”

Individual student-level characteristics such as gender, school belongingness, adult support and involvement in violence significantly impacted suicidal ideation for teens. However, school-level characteristics such as overall demographics and peer groups had a greater impact, contributing more than double to explained variance in suicidal ideation. The overall composition of the student body, for example, may be more indicative of the risk of suicidal ideation among students in a school than an individual teen’s race or ethnicity.

“This has a clear implication for the state and national educational system,” said Benbenishty. “Look for schools with extremely high rates of suicidal thoughts, focus on them, and provide resources to help them engage in preventive work.”

Nationally, suicide was the second leading cause of death among 15- to 24-year-olds in 2015. The age-adjusted rate of suicide for 15- to 19-year-olds was approximately 10 per 100,000 population, with rates of suicide among young men and young women steadily increasing. Although young males had higher rates of suicide, females in high school were more likely to consider attempting suicide and to make a suicide plan.

Go to a tabular version of suicide in high school at the bottom of this page.

Teen Suicide Prevention Strategies

Astor, Benbenishty and Roziner’s study highlights a problem in how suicide is addressed in schools in California and across the country.

“[Suicidal ideation] is really conceived of and thought of as an individual issue and treated as a counseling, psychological or medical issue,” said Astor. “But the school is not just a place where you find kids with mental illnesses and deliver services. It’s a place where you have to address the actual peer and social dynamics that contribute to higher suicidal ideation.”

Based on their analysis the authors believe suicidal ideation needs to be tackled with a public health approach in schools. Instead of focusing on the individual, schools need to focus on the entire community and environment, supporting students from both an educational and a socio-emotional perspective. That requires making sure the entire school staff, including teachers, principals, bus drivers and cafeteria workers, understand the dynamics within high risk schools and are prepared to intervene when they see individuals who may be at risk. Adults, including parents, need to be educated about how to respond when a student says they want to die.

Similarly, schools have to address issues of secrecy among peer groups. Peer groups may be more likely to know a friend is thinking about suicide or has attempted suicide than staff at the school due to privacy policies. Students need to understand the importance of referring friends when they say something of concern. Astor added that schools should make sure staff is trained on how to handle such referrals.

He also worries there may be a strong contagion factor within school peer groups and perhaps even faculty.

“Once you hit a tipping point of say 30 or 40 percent of kids just talking about it in the cafeteria, it may get normalized,” he said. “If there are suicidal attempts and they are not responded to correctly either by the faculty or their peers, it gets normalized and could give it more legitimacy.”

Further studies on peer group dynamics and the question of tipping points related to the number of students who have suicidal ideation in a school can help schools determine the types of resources, staff training, expertise, community supports and programs they need, Astor explained.

Using Peer Groups to Address Suicidal Ideation

Astor believes schools can work with peer groups to help save students’ lives by focusing on school climate.

“You’ll see kids with mental health problems say ‘I need another school, I need a place where kids are nicer,’” he added. “And it’s not just about bullying. It’s about being part of something.”

Focusing on making schools more welcoming and more accepting between peer groups and school staff is one way to help high-risk groups. Astor suggests developing extracurricular activities that emphasize school connectedness and acceptance. He also suggests paying close attention to new students transitioning into schools who may feel isolated or stigmatized and have difficulty making friends, leaving them vulnerable to joining risky peer groups.

Astor, who co-authored “Welcoming Practices,” with Benbenishty has helped train teens how to welcome new students into a school, ensuring that transitioning students have a positive peer group to help them through their first couple months. With teachers’ and principals guidance, the students can offer simple support such as a place to sit in the cafeteria or tutoring to help prevent them from falling behind academically. This kind of support may be minimal but it is also important for teens who may be heavily influenced by their peers, he says.

“The next step for the research team is to compare schools that have similar school-level characteristics but different levels of suicidal ideation in order to determine why certain schools are addressing the problem better than others,” said Roziner.

The team hopes this will lead to a more effective strategy to deal with suicidal ideation that zeroes in on problematic areas within high suicide ideation rate schools.

“You go where it’s the hardest hit. And that’s kind of a different strategy than what the country is doing right now. They are kind of providing FYIs to students, educators and parent and they can take it or leave it as information,” Astor said. “Why not target a smaller number of schools and at least take care of this problem in the most extreme places?”

Additional Resources from Professor Astor

Changing schools can be a stressful and disruptive life event for students and their families. Welcoming Practicessummarizes research on school transition issues among students K-12 education levels and provides social workers, psychologists and educators practical strategies to developing and implementing welcoming practices for new students before their first day at school, which can help dramatically reduce social isolation among new students.

‘Mapping and Monitoring Bullying and Violence’

This step-by-step book serves as a guide to help pupil personnel, school district and school education leaders reduce incidents of violence and bullying through mapping and monitoring techniques that provide a visual record of school physical spaces considered safe, alongside those that students view to be places where they might encounter bullying, harm or trouble. Mapping and monitoring practices have significantly helped reduce incidents of violence and bullying in California, Chile and Israel.

Use the promotion code ASFLYQ6 for 30 percent off the purchase price. Royalties from “Welcoming Practices” and “Mapping and Monitoring Bullying and Violence” will be donated to anti-bullying programs in the U.S. and abroad.

If you or somebody you know is struggling with mental health issues or suicidal thoughts, please call the 24/7 National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255, which is free and confidential, or visit the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline site.

The following section contains tabular data from the graphic in this post.

Suicide in High School

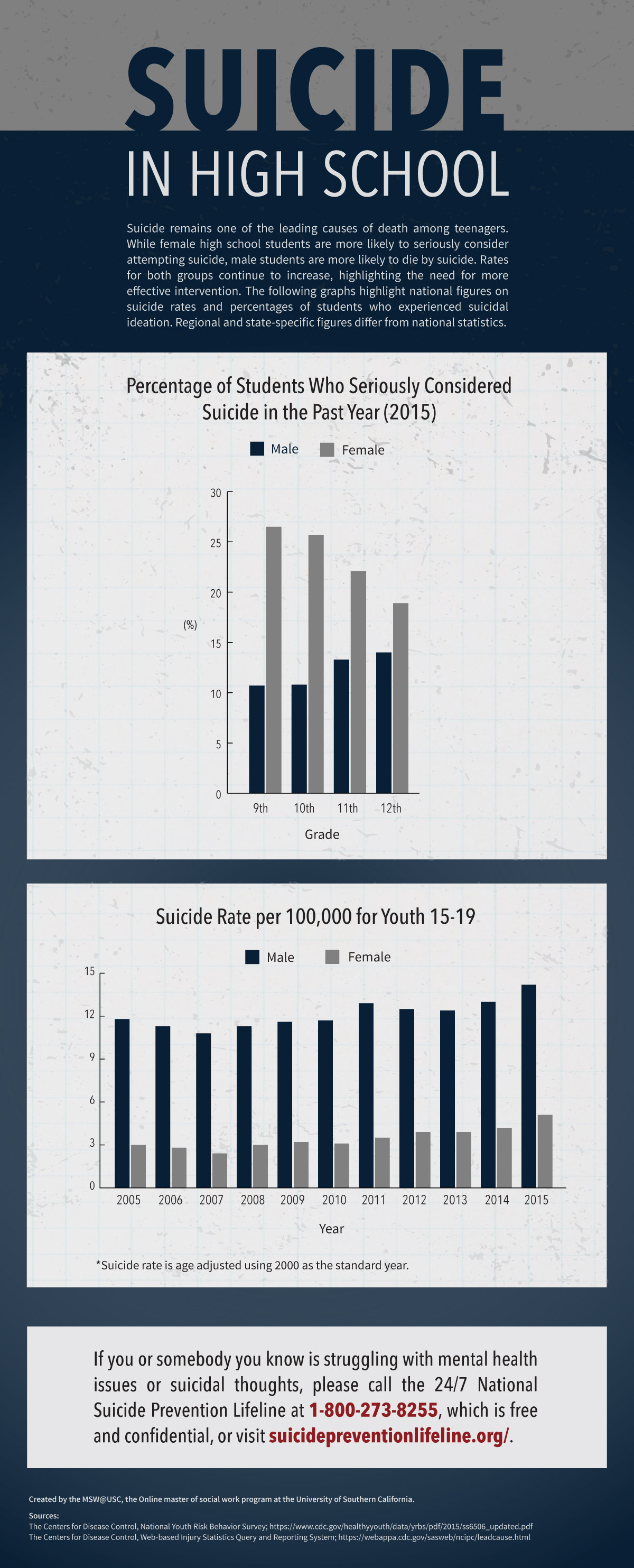

Suicide remains one of the leading causes of death among teenagers. While female high school students are more likely to seriously consider attempting suicide, male students are more likely to die by suicide. Rates for both groups continue to increase, highlighting the need for more effective intervention. The following graphs highlight national figures on suicide rates and percentages of students who experienced suicidal ideation. Regional and state-specific figures differ from national statistics.

Percentage of Students Who Seriously Considered Suicide in the Past Year (2015)

| Grade | Female | Male |

|---|---|---|

9th Grade | 26.5% | 10.7% |

10th Grade | 25.7% | 10.8% |

11th Grade | 22.1% | 13.3% |

12th Grade | 18.6% | 14% |

Suicide Rate per 100,000 for Youth 15-19

| Year | Female | Male |

|---|---|---|

2005 | 3 | 11.8 |

2006 | 2.8 | 11.3 |

2007 | 2.4 | 10.8 |

2008 | 3 | 11.3 |

2009 | 3.2 | 11.6 |

2010 | 3.1 | 11.7 |

2011 | 3.5 | 12.9 |

2012 | 3.9 | 12.5 |

2013 | 3.9 | 12.4 |

2014 | 4.2 | 13 |

2015 | 5.1 | 14.2 |

Back to suicide in high school graphic.

Sources:

National Youth Risk Behavior Survey (PDF, 2.9 MB), The Centers for Disease Control

Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System, The Centers for Disease Control

Citation for this content: The MSW@USC, the online Master of Social Work program at the University of Southern California.